Effectual JS Pt 1: Rend(er) Me Asunder

If we’re going to build a full JavaScript framework from scratch, we need to start somewhere. Personally, I like having tangible results up front, so let’s start with the bare-minimum needed to create a visible webpage — let’s start with the rendering engine!

The State of the Art

You Keep Using That Word…

When I use the term render, you might immediately call to mind a college graphics course where you brute forced some matrices to draw a triangle on your screen.

In the web development world, however, we usually don’t mean it in that context. Instead, rendering often refers to the problem of taking our code and converting it to something that can be displayed in the browser.

Specifically, rendering is the process by which JavaScript components are converted into an HTML representation. This process is necessary in any web development framework, and will be the first thing we tackle in Effectual.

The Virtual DOM

Everyone loves a good virtual DOM, right?

No? No!? That’s ok, we can love it in their stead. But to truly love something is to understand it and accept it for what it is. So what is the virtual DOM?

The OG DOM

Consider first, the real DOM — the Document Object Model used by the browser to represent HTML elements both as objected rendered to the screen and as entities accessible and manipulatable from a JavaScript context.

When you load the following webpage in e.g. Chrome

<body>

<div id="root">

Hello <b>World</b>

</div>

</body>

The browser parses your code and creates a series of DOM objects (the div, the bold element, and two text nodes representing our content.). These are then accessible to use via JavaScript, for instance by executing document.getElementById("root").

Once held in JavaScript, we can easily add nodes, delete nodes, or modify them as we like.

Given this, let’s reconsider the virtual DOM.

A Bittersweet Reconciliation

A virtual DOM, in constrast, is any secondary representation of the DOM’s structure (usually a tree of JavaScript objects). These objects are purely informational, they could store the tag and the props of the object but the rendering context knows nothing about them.

A common approach taken by several rendering engines is to first generate a virtual DOM and then reconcile that virtual DOM against the real DOM.

The natural question in this scenario is why one would bother with the intermediate representation instead of just creating the real DOM elements and manipulating those. The answer to that question lies in that reconciliation.

DOM elements are expensive. They’re expensive to read; they’re expensive to write. Furthermore, we’re potentially making updates at 60 FPS. if every frame needed to recreate the DOM state from scratch, we’d be doing an absurd amount of work.

Instead, on every frame we want to update exactly those things that changed. This reconcilation of the old state to the new lets us only update those things that were actually modified, saving on 99% of the work we do during render.

A Cheap Imitation

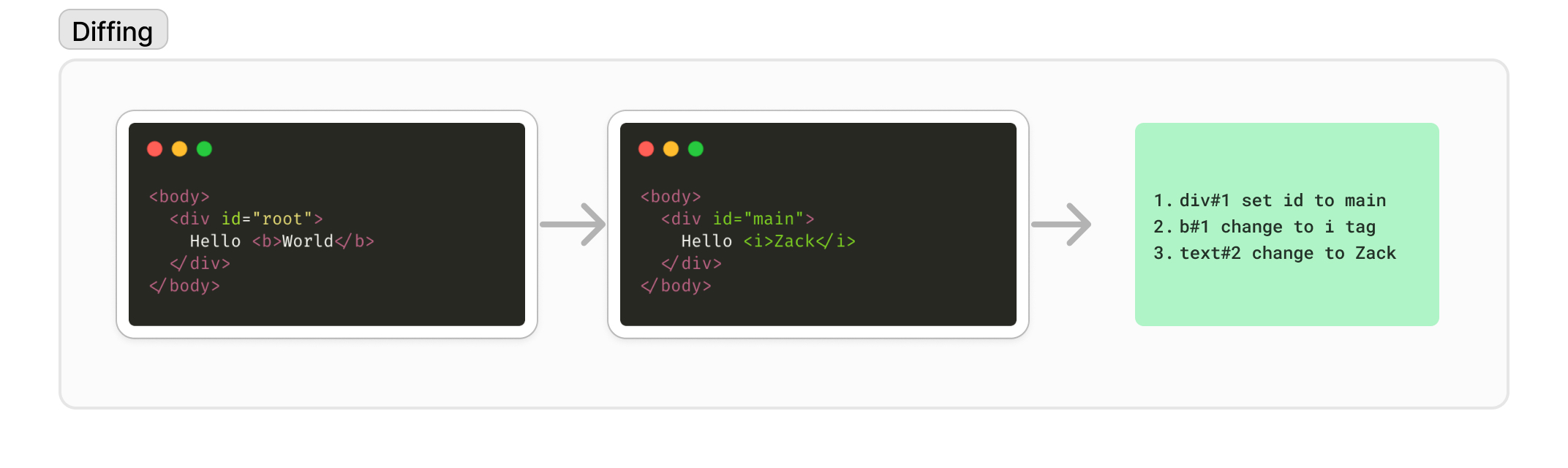

This is where the virtual DOM can come in handy. At some point during this process, we must ask “how do we know what changed?” Once approach is to take a diff between the newly proposed state and the extant DOM.

However, as we mentioned previously, even reading DOM state is expensive. Thus, in order to compute that diff we can instead first render our code into a inexpensive virtual DOM, use that to compute updates, and then apply those updates to the real DOM.

Naively this approach (which I’ll impudently dub “the React approach”), is quite easy to understand and then reason about. Roughly speaking, it works like this:

- Render the application to the virtual DOM

- Diff the previous vDOM with the new vDOM

- Apply those diffs to the actual DOM

However sometimes conceptual simplicity can lead to downstream complexity.

Did you get my Memo?

That first point in particular obscures just how much work could go into rendering the application. Every frame the renderer needs to completely re-run all of the code used to render.

To understand this, let’s formally define a component. We’ll say that a component is a piece of JavaScript code that computes a tree of nodes, each of which is either a native HTML node or another components.

In React, components are often just functions that return the tree:

const MyComponent = (props) => {

return (

<div>

<span>Here is:</span>

<MyOtherComponent name={props.name} />

</div>

);

};

Or in Vue (which uses Single File Components), you might have

<template>

<div>

<span>Here is:</span>

<MyOtherComponent :name="props.name" />

</div>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts"></script>

Although they do so differently, these are both effectively just pieces of (weird looking) JavaScript that describe trees of nodes.

However, since they’re just JavaScript, they can perform arbitrarily hard work. Even if they don’t, large amounts of a little work can easily add up.

To address this, we want our renderer to reuse as much previous work as it can. In other words, we want to maximize it’s ability to memoize state. However, depending on the framework this can require a lot of manual work on the programmer, and is a large source of added complexity stemming from a simple design.

A Survey of Forms

Most of this discussion so far has been oriented around the virtual DOM because (spoiler alert!) that’s what I want us to implement. However, now that we understand it a bit better, let’s step back and look at various vDOM approaches and non vDOM alternatives.

First of all, the React style is great for discussing the vDOM because it’s easily digestible. However, Vue’s vDOM implementation is quite cute and worth discussing further.

Because Vue uses a custom compiler for its Single File Components (SFCs), and because the templates are static objects, it can make a lot of guaranties about how the intantiated component will map to the resulting node tree.

These guaranties let it know exactly which DOM elements the nodes map to, so the reconcilation approach only needs to re-evaluate the nodes that actually changed — children of an updated component don’t inherently change just because their parent did.

Contrast this with React whose components render an arbitrary tree each time and so by default it needs to re-render all downstream components as well.

Consider further Svelte, which takes the Vue approach one step further. Also employing a custom compiler for a static template, Svelte doesn’t even bother rendering the component into a vDOM, it just immediately flushes those changes to the DOM!

The Vue and Svelte style approaches are great because they save the runtime a lot of work, but they have the inherent drawback of requiring a custom compiler. In general, I don’t care for compilers. Not only do they add an extra step to the compilation process, they introduce an incredible amount of additional tooling (which can be flaky sometimes :sadparrot:). My biggest complaint with the addition of a custom compiler, however, is that they have a tendancy to obscure the semantics of the code. Ultimately, the simpler the semantics of a program are, the easier it is to reason about correctness.

Building it Ourselves

Our Approach

Now that we’ve explored various vDOM implementations and their pros & cons, how do we want to build our renderer?

For the astute reader, you already know that we’re intending to use a vDOM. Furthermore, for simplicity’s sake we’ll implement this vDOM in the “React style”.

However, before just naively re-implementing React, we should ask ourselves whether we can do better. The main drawback to React is that it either performs an inordinate amount of work every render, or requires the programmer to go out of their way to ensure components are memoizable.

Since we have full control over our framework, let’s add a stipulation to our requirements:

All components are memoized by default!

Let’s think through what this entails.

Right now, without a reactivity engine, a component can only change if and only if its props change. Thus, a naive solution here would be to memoize all of its props, store them along with a cached version of the previous render, and reuse the entire subtree if possible.

Obviously, it’s not that easy. Consider this pure component (written React style)

const MyComponent = () => {

return (

<SomeOtherComponent name={"Zach"}>

<div>Hello World!</div>

</SomeOtherComponent>

);

}

In React, SomeOtherComponent would receive two props. The first is name whose string value is a constant and thus easy to memoize.

The second, however, is children with the value of <div>Hello World</div>. “But wait!” one might ask, “what even is that value??”.

The convenience JSX offers obscures an ugly truth. Every node you create in your tree is nothing more than a function call to React’s _jsx function. That nice little component is simply:

const MyComponent = () => {

return (

_jsx(

SomeOtherComponent,

{ name: "Zach" },

_jsx(

"div",

null,

["Hello World!"]

)

)

);

}

Unsurprisingly, subsequent invocations of _jsx (even with the same parameters!) will return referentially-unique objects. That means for compoents who take children, we are unable to memoize their props!

So are we DOA? Well in React’s case the answer is generally just “yes.” You can only memoize those components that do not take any children arguments. Yet, by taking a page out of Vue’s playbook, we can do better.

Slots 🍒🍒🍒

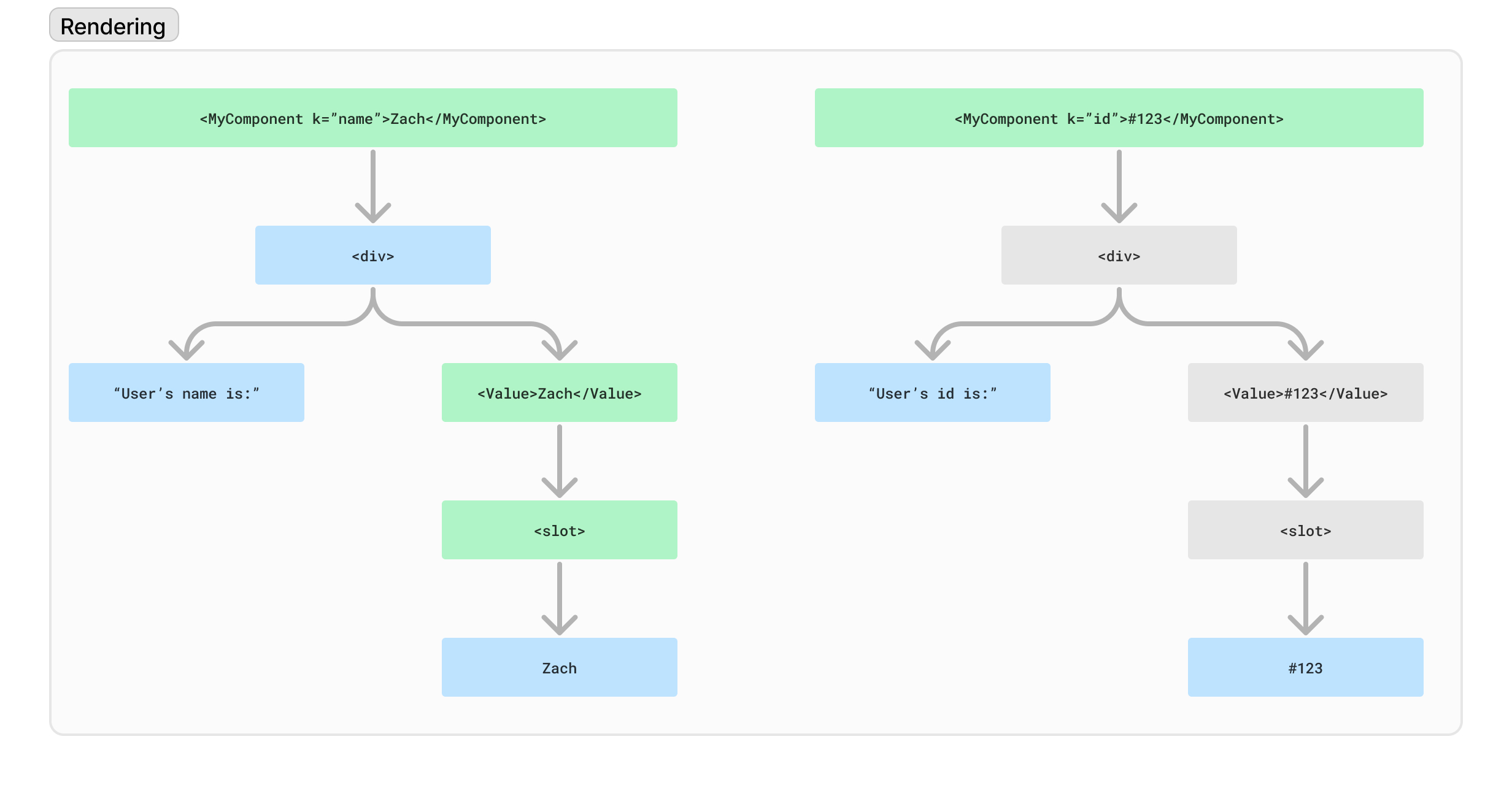

Unlike React, Vue doesn’t pass children via props. It instead passes them via a generalized “slot” interface. Components can define one or more slots, and then their invokers will specify content for each of those slots.

When the component renders, it first computes all of its internal state. Then, the rendering engine searches the tree for those slots and substitutes in the content from the caller. However, because the original component was unaware of the contents of those slots, changing the value that fills them does not require the component to rerender.

I’ll refer to this property as middle-out memoization. By removing children from props, and instead supporting a slot interface, we can augment the React-style virtual DOM with middle-out memoization that justifies a memoization-by-default policy.

The Rendering Algorithm

Now that we’ve designed an approach (React style vDOM + middle-out memoization), we can implement our rendering algorithm.

The Effectual algorithm can be found here in fullness, but I’ll briefly summarize the algorithm here:

- The very first pass, we expand all components directly into vDOM nodes

- Components are invoked to return a node tree

- The results of that tree are collapsed into a list of DOM nodes and component nodes

- We recurse on each of them, copying over DOM nodes into the output and rendering component nodes into their sub-tree

- On the second pass, we expand the components in the context of the previous expansion

- We start in the “dirty expansion path”

- When we encounter a component, we check to see if its props are the same as before. If so we enter the “clean expansion path”. Otherwise we invoke the component and remain in the “dirty expansion path”

- As before, once we render the component we flatten its results into a list of nodes. However, this time we also compare the list to the previous render’s result list.

- We then try to match elements from the current render to the previous render, by looking for a “key” property that can be used to align the two

- If we’re able to find a match, we continue expanding in the context of that match. Otherwise, we expand as though this were a brand new subtree.

- Otherwise, we may enter the “clean expansion path”

- Once in the clean path, we keep reusing old nodes until we hit a custom component. Once we find such a component, we check an

isDirtyflag (currently unimplemented), to see if something else tainted the component. If it did, then we re-enter the dirty path - Otherwise we continue recursing down the clean path.

- Once in the clean path, we keep reusing old nodes until we hit a custom component. Once we find such a component, we check an

- We start in the “dirty expansion path”

Looking forward

Now that we have a basic rendering engine, we can use it to render a very simple website! All that’s needed is to render the resulting vDOM nodes to a string and then write that string to document.body.innerHTML.

You can check out these results at effectualjs.com (it’s gorgeous, I promise), and continue to check back as we plan to build out the next phase of Effectual: our reconciler!